🎯 TL;DR:

Identify the different communities of users for your product, hang out with them (online or offline) to assess likes/dislikes/trends, and mull over things (with the help of some frameworks).

In Well-Designed, Kolko puts forward the idea of a market as being a community of people (users, policy-makers, competitors etc), and the often-used phrase ‘product-market fit’ as being how this community responds to the product in question.

The best way to thus understand the market is to hang out within its different communities (of users) and look out for signals that could help in crafting a compelling product differentiator. Example: What do these people currently do and how do they do it? What do these people gripe about? What do they wish for? And more importantly: Are there any major shifts in attitude and practices?1

Signals, when taken as a whole, can give rise to unique insights about a market and enable you to carve out a spot for yourself. In my case, the nature of the product that I was looking into—consumer-driven, marketplace for talent, something all of us could relate to—made empathising with the user more straightforward. Having done a coding bootcamp, I also had ready access to an active alumni community hunting for opportunities in tech and was broadly aware of the topics that were usually discussed. I have also previously written about studying a user group that I was interested in through actively engaging in relevant Facebook groups.

But be aware that some signals such as competition and what they are up to are merely noise. It is, of course, useful to know something about what you are up against but concentrating too much on what others are doing distracts you from what they aren’t. Moreover, it is nearly impossible to replicate the character of a product that a competitor has built which in itself is a reflection of the company’s culture and values (Microsoft products, for example, are very different to those of Apple). Blindly keeping track of features and copying them, in addition, only results in a poor user experience. 2

Once you’ve gathered your signals, you can use certain tools to make sense of them. The tools or, as Kolco calls them, working artifacts help you mull things over and slip into a sense of exploration. They can also help you filter out signals that don’t fit in with your broader goals. For those exposed to consulting frameworks, these tools aren’t exactly used to communicate your ideas/findings to anyone, but to doodle, explore options and get into a creative headspace.

I’ve outlined below some of the tools that I used to consider my vision/strategy: value-goal statements, user-attribute matrices and pre-mortems.

Why am I building the product? How would this fit into universal themes such as love, connection, respect, pride etc? Thinking of yourself being in charge of a value rather than a product can be a means of filtering what you don’t want to focus on.

As an example: I help connect untapped tech talent in Africa with world-class opportunities in Europe. Unlike LinkedIn, our talent profiles are internally vetted and the employers who use our site are actively looking to hire African talent. Essentially: plugging the gap between talent and opportunity.

These are 2-by-2 diagrams to tease out any relations between different communities. The first step is to identify the different groups of users who might be using your product. The second is to ascertain what differentiates them so that you can make a list of factual and emotional attributes. The third is to plot these attributes against one another to generate insights: areas that are best avoided or best explored from a positioning perspective.

These steps are best illustrated by an example. For a job board focused on tech talent the users would be:

Supply |

Demand |

|---|---|

| fresh grads (either university or bootcamp) |

Startups (founders, engineering lead) - Early-stage: focus on MVPs etc - Scale-ups: established product-market fit, and tech teams |

| professionals (full-time or freelancers) |

Large corporations (HR, hiring manager) - Tech as focus: SaaS - Tech as an enabler: banks, government organisations, charities, companies in traditional sectors going for a digital presence |

|

|

Recruiting agencies (Headhunters) |

|

|

Web/design agencies |

Comparing one group against another might help generate attributes. For example: what would differentiate a resource-strapped, growing startup from an established company? It might be the budget available or the level of supervision that can be afforded to a new hire or it could be the flexibility when it comes to where you can work from. The table below summarises some of the attributes that I came up with.

Factual |

Emotional |

|---|---|

| Cost of hiring (budget available) |

Uncertainty over fit |

| Quality of work produced |

Uncertainty over work output |

| Level of supervision required |

Uncertainty over working mechanisms |

| Work location |

Sense of working together |

| Availability/variety of profiles |

|

| User segment size |

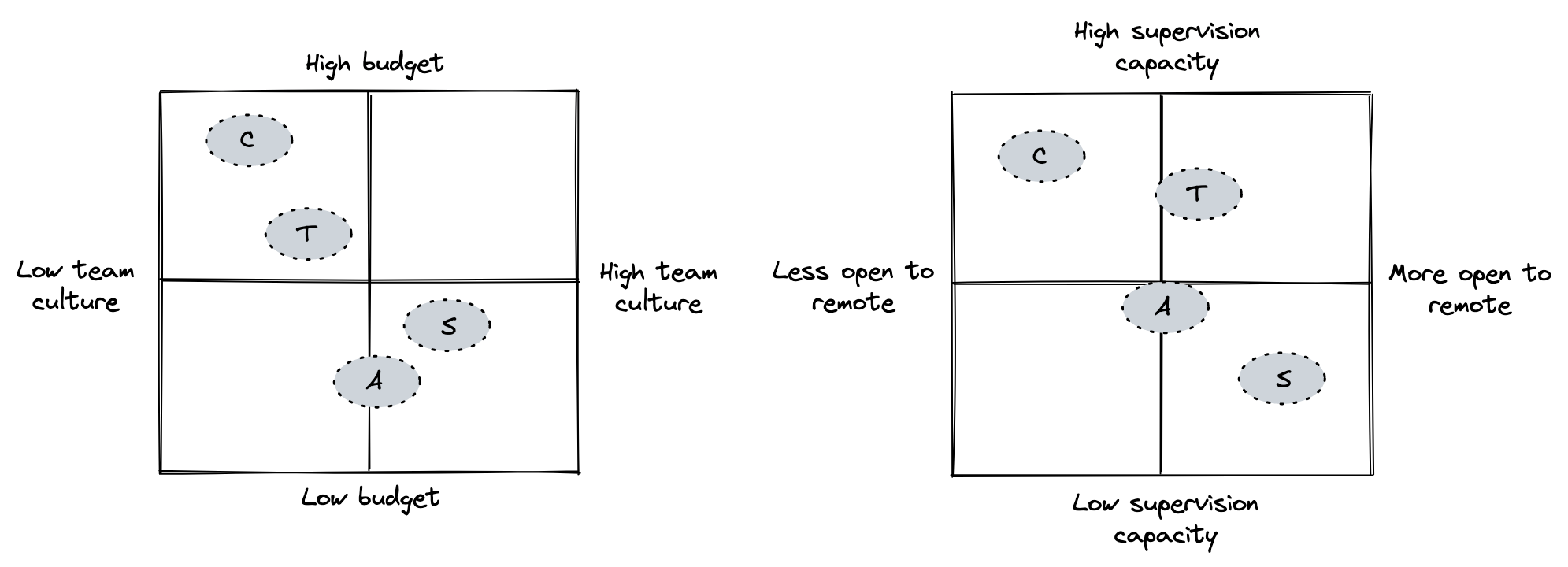

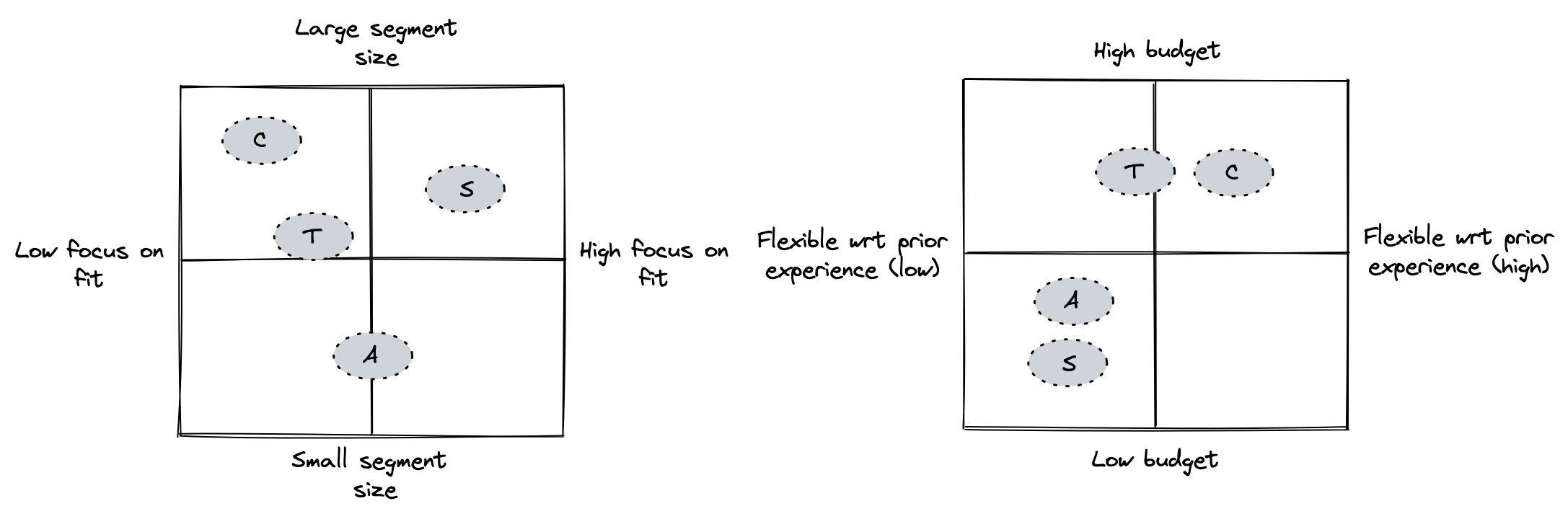

Based on the above attributes, the charts below depict some of the possible combinations. Mulling over them raises questions such as: Is there an opportunity amongst companies with a low budget but don’t have a strong focus on team culture (something like a SWAT team that goes in to work on a specified project/problem) or should we position ourselves as offering bright developers who don’t have much experience to companies on a shoestring budget. If it’s the latter, would that even work in practise considering that hiring managers automatically reject people without a prescribed length of experience?

Figure 1: Matrices to elicit insights (click to enlarge); S = startups, C = corporations, T = tech-focused companies, A = web/design agencies

Figure 1: Matrices to elicit insights (click to enlarge); S = startups, C = corporations, T = tech-focused companies, A = web/design agencies

Figure 2: Matrices to elicit insights (click to enlarge)

Figure 2: Matrices to elicit insights (click to enlarge)

If this product fails in the future, why would that have happened? Asking yourself this question early on forces you to visualise scenarios that could crop up in the future and thereby refine your offering before you go-to-market. In my case, these were some of the issues that I could identify:

- Companies not being open to temporary, remote staff, either because of policy or security

- Not able to source enough local talent who meet Western company specs (i.e. not enough relevant experience, knowledge of the right languages)

- Talent not performing on the job

- Costs of the new hire not a dealbreaker to most tech companies, whereas capability is

- Pricing not in line with employer expectations

- Apart from cost, the product doesn’t offer anything new compared with other tech-focused job sites

To wrap things up, the first step in building a product is immersing yourself in your target market and getting a feel for the macro picture: community trends and market forces. The next step is to deep-dive into individual behaviour and understand the needs and wants on a micro level.