The one thing I realised when trying to figure out what to build was how experimental, iterative, and subjective the whole process tends to be. I doubt if anyone who launches a successful product ever does so fully knowing what form it would finally take or if it would ever go down as intended with their target user base. Of course, there are well-known examples of now household brands having to change course when they first started: Instagram, for example, began as a location-sharing app.

But reading is one thing and living through it is another.

I have summarised below my experience in figuring out what to build in the EdTech space and the lessons it reinforced. I call it reinforced because, through reading/classes, etc., some version of these lessons had been wedged in my head but being in the thick of things brought them to the fore and threw a whole new set of challenges that showed product discovery in a new light.

Lesson One: First, own the problem space

Fresh from a coding bootcamp, I was raging to put my newfound skills to practice. I plunged into action and settled for one of the first product ideas that came to my mind: an online assessment tool for school teachers. Given the media coverage of the pandemic’s adverse effects on school education at the time, I suspect that the world around me might have subconsciously influenced me. That, and a soft spot for the education sector in general. The goal was to improve my coding skills; why bother thinking too much about what I was going to build?

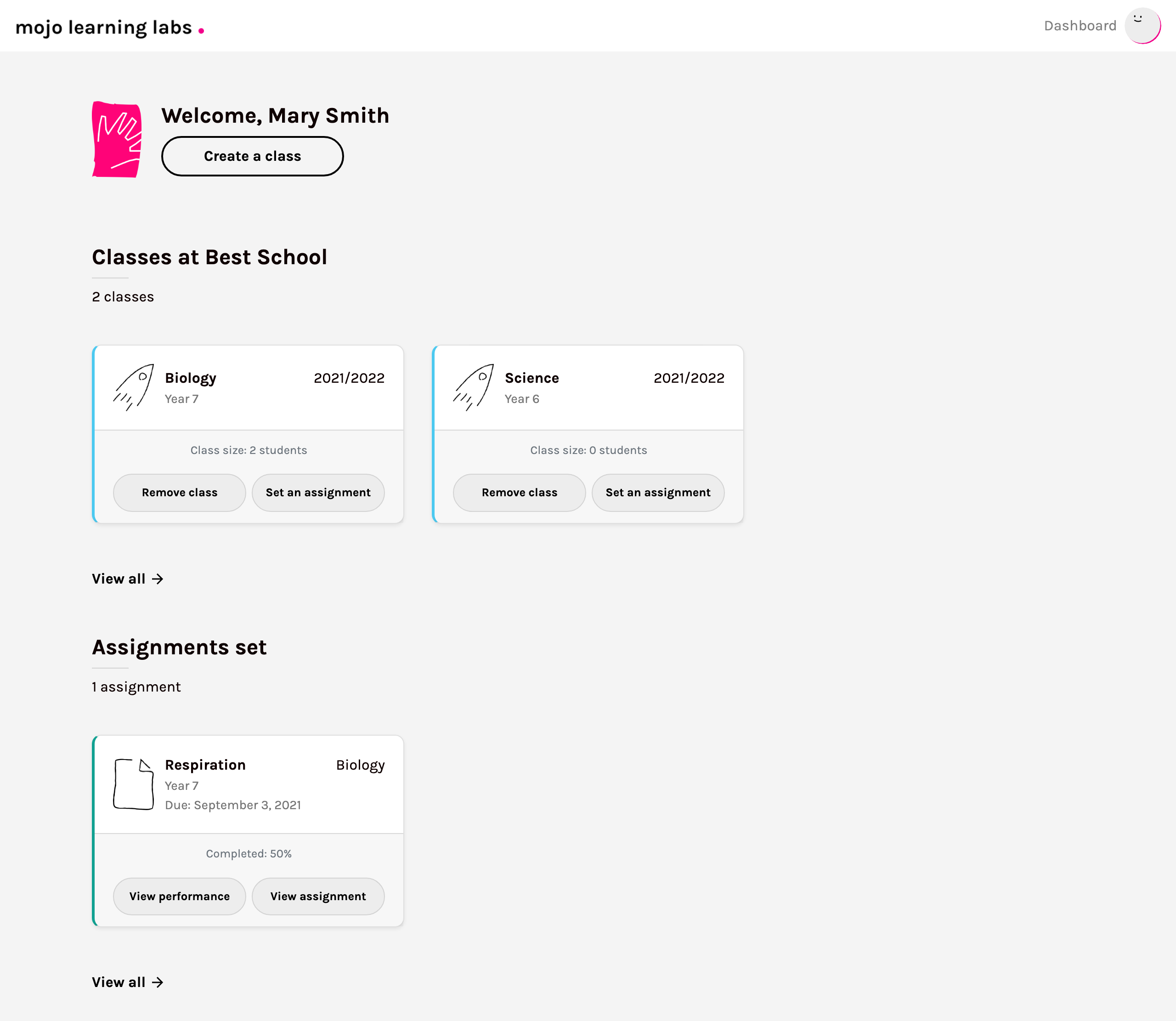

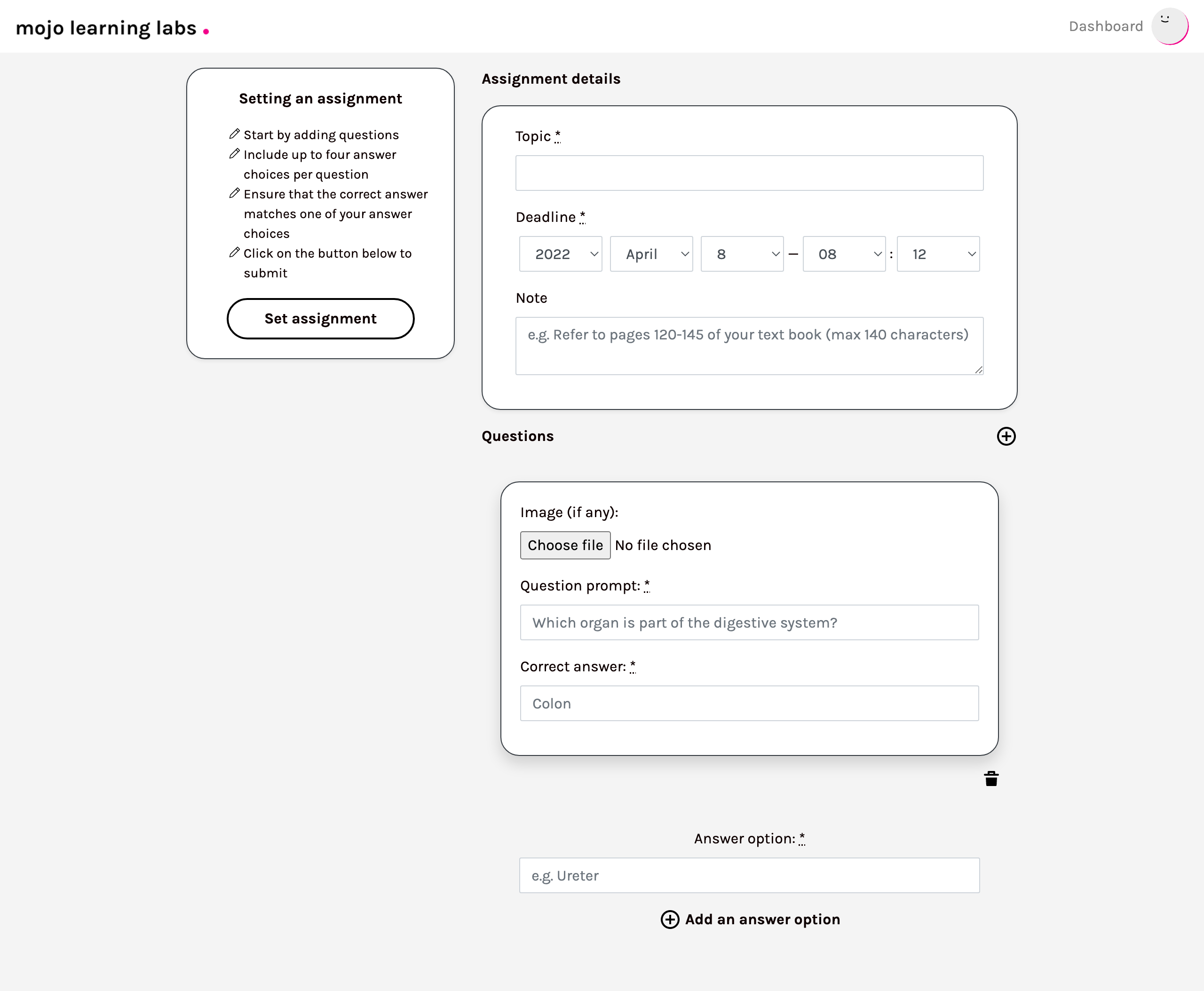

Idea in place, I rolled my sleeves and started building the web app. The struggles faced in this endeavour and the associated learnings should be an entire article in its own right but suffice it to say that once I had emerged from many a rabbit hole that I had dug for myself, I had a shiny new tool that (a) looked good (I had paid attention to basic UX/UI) and (b) did what it was meant to do. My line of thinking about the product being a non-issue would have been fine if I had stopped it at that. Alas, not. Chuffed by what I had managed to build on my own and swept away by my optimism, I reached out to a few schools and set up meetings to show them my handiwork. For some reason, in that adrenaline-fuelled moment, the image that I had in mind of a teacher was the one that I had encountered at school: not very tech-savvy nor open to embracing the tools of the future.

It was an awakening when, after patiently listening to my product demo, the first teacher asked me how it differed from Google Classrooms. I remember mumbling about the app being more intuitive and easier to use. But, I knew in my heart that it was not a compelling reason for anyone to undertake a significant shift in their way of working. Another conversation with another school went the same way. It took a moment of discomfort to sink in that schools had adapted for the pandemic and that I was putting the cart before the horse. Indirectly, I’d embodied what those with some technical skills fall prey to: rushing to build. I should have first immersed myself in that space, identifying schools’ needs/problems/desires and whether they were painful enough for them to resolve by paying money. The target user base and their problems should have come first.

The conversations weren’t a total disaster though. I switched gears halfway through and used the opportunity to find out more about the issues teachers faced when setting homework. I learnt that creating assessment material/questions was time-consuming and that marking long-form answers was another. These were problems not addressed by products such as Google Classrooms or Microsoft Teams, and would probably never be. However, I knew many products in the market addressed these issues in various ways. Was there a gap in the market? Or was there something that current players don’t cater fully to? My curiosity now stoked, I parked my app to one side and tried to better understand the secondary schools space.

Lesson Two: Get creative when trying to understand and connect with your target audience

I must have had crude luck when sourcing teachers for my first two conversations. Or I could only get their attention by referring to the product I had built. I quickly discovered that cold emails where I asked for time for research mostly went unanswered. Even the attempts to source conversations through my networks were unsuccessful: the teachers were either sceptical about confidentiality issues or couldn’t find time to chat. Perhaps it might have been different if I had given some incentive such as gift vouchers, but I didn’t want to go down that route.

Searching for alternative means of connecting with the target user base, I discovered several Facebook groups that brought together teachers with various interests and backgrounds. There were several for science teachers, online tutors, and even one for parents prepping their children for competitive school exams. I joined all the groups I could find including related ones like those for parents who homeschool their children. I now had a means of engaging with the people I had been struggling to connect with.

I spent a few weeks taking a back seat and quietly reading some of the posts that cropped up in the group and the comments those posts garnered. One of the science groups was particularly active; the posts ranged from asking where to find assessment questions to ideas for practical work to help with lesson planning. Once I figured out the lay of the land, I posted a simple question to the group: What were their biggest issues when it came to teaching science?

Judging by the number of responses generated within a few hours on a Sunday morning, I had struck a chord. Replies ranged from the workload associated with ongoing assessments to how broken science teaching at school was (“My degree is in biology, but I have to teach physics as well”; “We just don’t have the time to make science relevant”; “I sometimes have to teach maths as well because the maths teacher hasn’t covered the topic yet.”). Having been a science student myself, I could relate to why providing an effective science lesson was a challenge to most teachers.

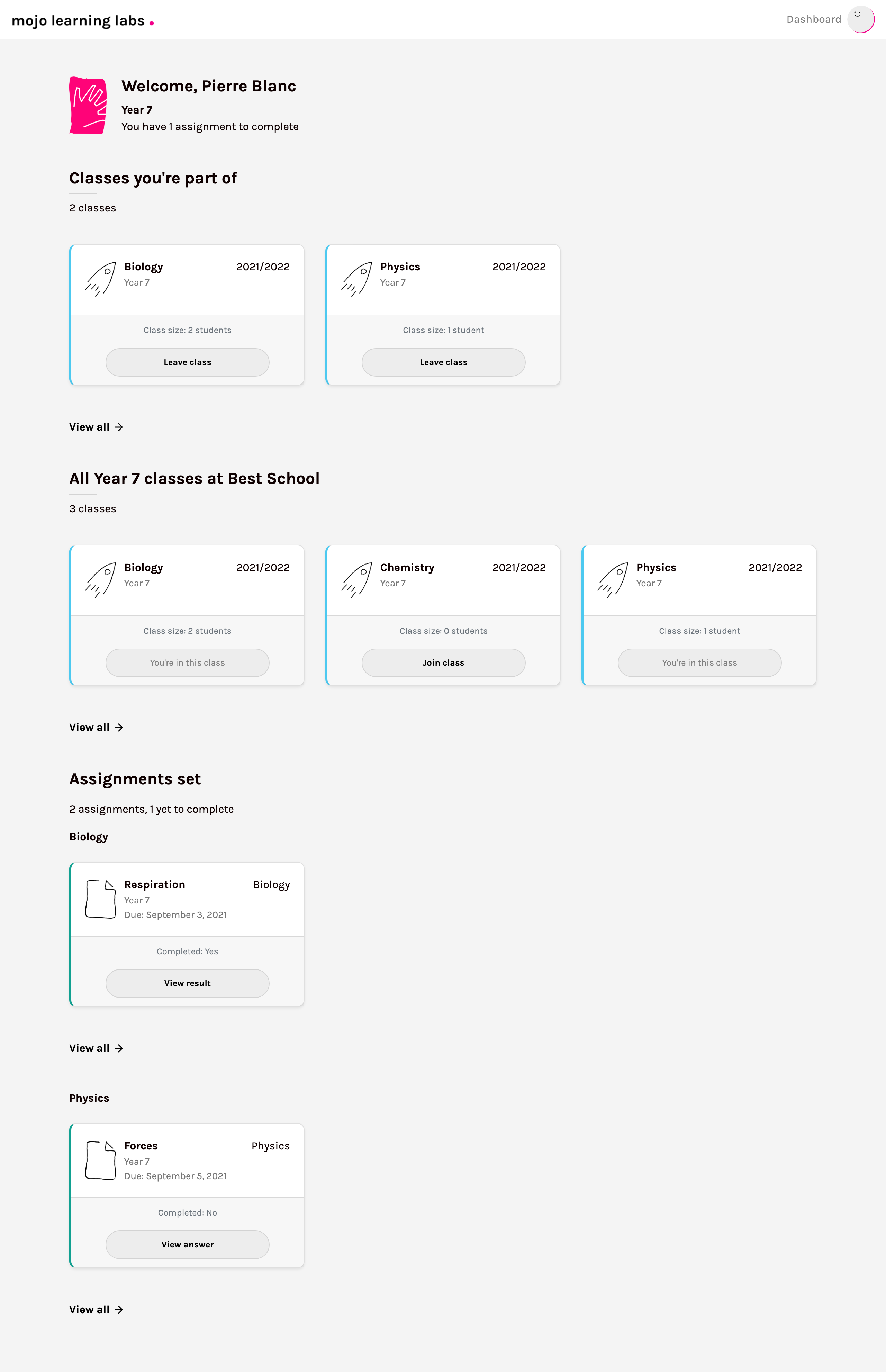

Lesson Three: Looking for and talking to users tells you something about the sales process as well

The replies from science teachers allowed me to think a bit more about what they were trying to achieve, or as a popular framework puts it, their ‘jobs to be done’ when teaching science. I could garner enough empathy to see the other side of the coin as well; the jobs students were trying to get done when trying to learn science. Merging them gave me an inkling of an idea to test. But which segment do I focus on? Should I build a product for schools/teachers (i.e., B2B) or should it be something for students (B2C)? My experience in trying to source teachers for interviews was eye-opening and made me rethink who I wanted to target. If having a simple conversation with schools and teachers was so arduous, how difficult would sales be when it comes to that stage?

Again, to test my hypothesis, I created a landing page highlighting some key problems (distilled from my user research) and shared the web link on the Facebook groups I was part of. Within a week, I had about fifty people who had signed up to receive a notification on launch. Fifty with whom I could have one-on-one conversations to refine the idea or stumble upon new ones.