How do you know if an idea has wings?

Having spent a considerable amount of time working with various founders—from newly-minted PhDs to those with corporate experience—I’m constantly amazed by the leaps of faith that they have taken. Sometimes, their efforts have paid off and their ventures have found steady ground. Sometimes, not so. And, frankly, I have at times asked myself what signals they looked at to convince themselves about their startup idea before investing the time, money and effort they did.

I’m aware of the ‘test and learn’ methodology that books such as The Lean Startup have popularised. But what if you have multiple ideas that you want to test out? Isn’t ideation all about generating several ideas and then comparing and contrasting them? Do you build landing pages and prototypes for each and test the market reaction?

Luckily, Teresa Torres’ book Continuous Discovery Habits has a simple solution for anyone faced with this dilemma: test assumptions instead of ideas.

I have previously written about building an assignment tool and realising that it wouldn’t have been an ideal solution for teachers who had gotten used to mainstream tools offered by Google Classrooms and Microsoft Assignment during the pandemic 1. If I were to take my own experience as an example, this is how I would have done things differently:

- Generate many ideas that can be compared and contrasted in the homework-assigning space

- Story map a selected idea with the main actors and their journey within the product idea in question

- Tease out the assumptions behind each step of the user journey

- Test the assumption

Working with several ideas

Regarding the assignment tool, the first mistake I made was not spending enough time on ideation or problem-scoping: I went with the first idea that came to my mind without generating enough alternatives in the opportunity space (How might we reduce teachers’ workloads?). I also relied on my own school experience to empathise with teachers and didn’t speak to any of them to understand their underlying needs. The first idea we come up with is generally not the best; the deeper we dig into the crevices of our minds, the more innovative our ideas tend to be. And, to whittle them down, ideas are meant to be compared and contrasted against one another (either on your own or as a group).

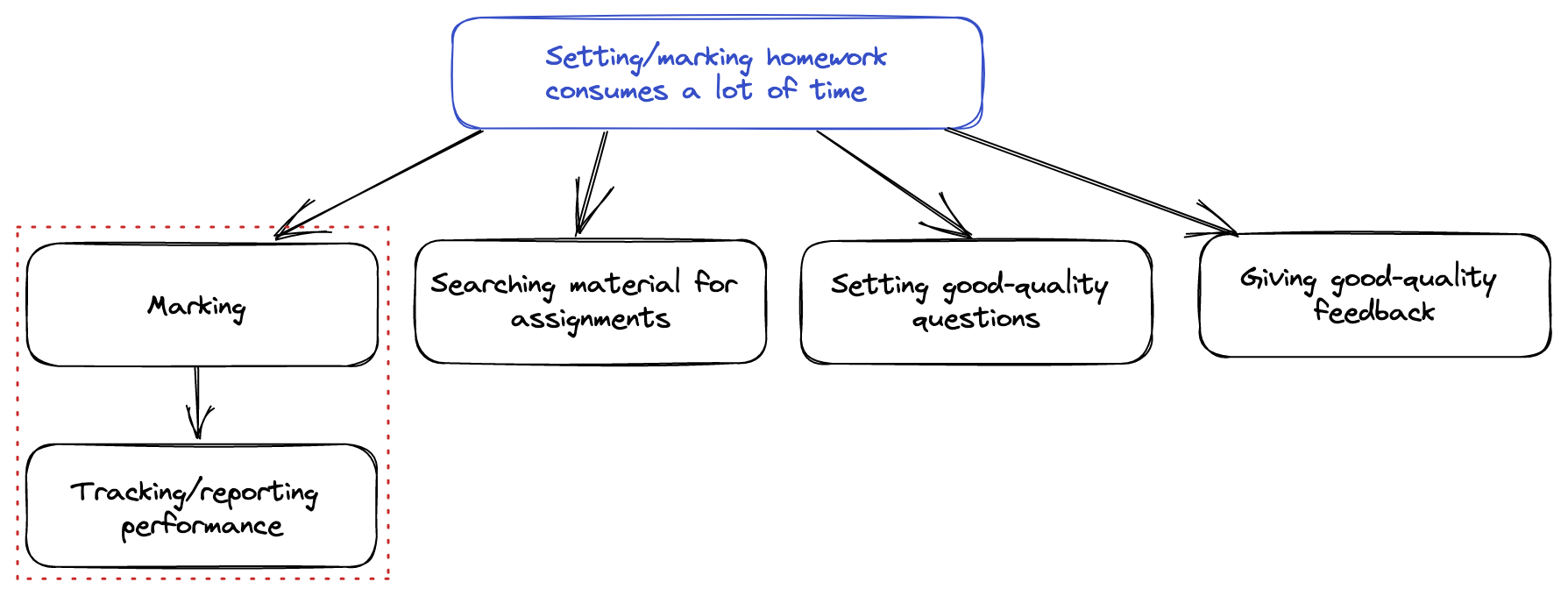

If making the homework process more efficient was the ultimate goal, the following diagram outlines the key areas that make it so from a teacher’s perspective. The highlighted part is the pain point that I was focusing on.

Pain points involved in assigning homework (click to enlarge)

Pain points involved in assigning homework (click to enlarge)

For illustration, some ideas that solve the marking/reporting problem are:

- a web app to set and score assignments to an entire class

- a mobile app that enables students to capture and submit homework; assignments marked by AI or some outsourced entity

- chatbot that allows interactive learning discussion to solidify concepts learnt at school

Since the above ideas all address the same problem, the underlying assumptions across all these ideas should be broadly similar.

Generating assumptions

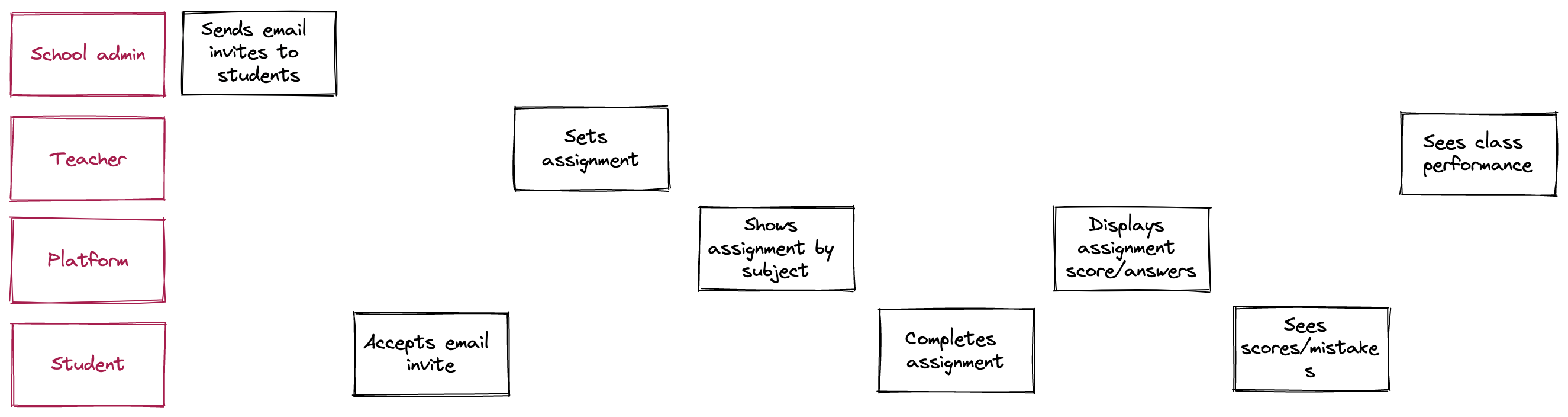

Once you’ve narrowed your list of ideas to the three that address the problem at hand, an effective means of understanding underlying assumptions is to pick one, pretend the product exists and story map the typical user journey. Below is a sketch that fleshes out what this journey might have looked like for an assignment-setting tool.

Assumptions, according to Torres, fall under five key buckets: desirability (do users want this?), viability (would users pay for this?), usability (can users find their way around the product?), feasibility (can we actually build this?) and ethics (are we allowed to do this?). Looking at each action through the prism of a major assumption category allows you to quickly generate a series of assumptions that you are taking at each step.

I’ve listed out some key assumptions that I’d subconsciously made when starting to flesh out the idea 2:

| Desirability |

|

| Viability |

|

| Usability |

|

| Feasibility |

|

| Ethics |

|

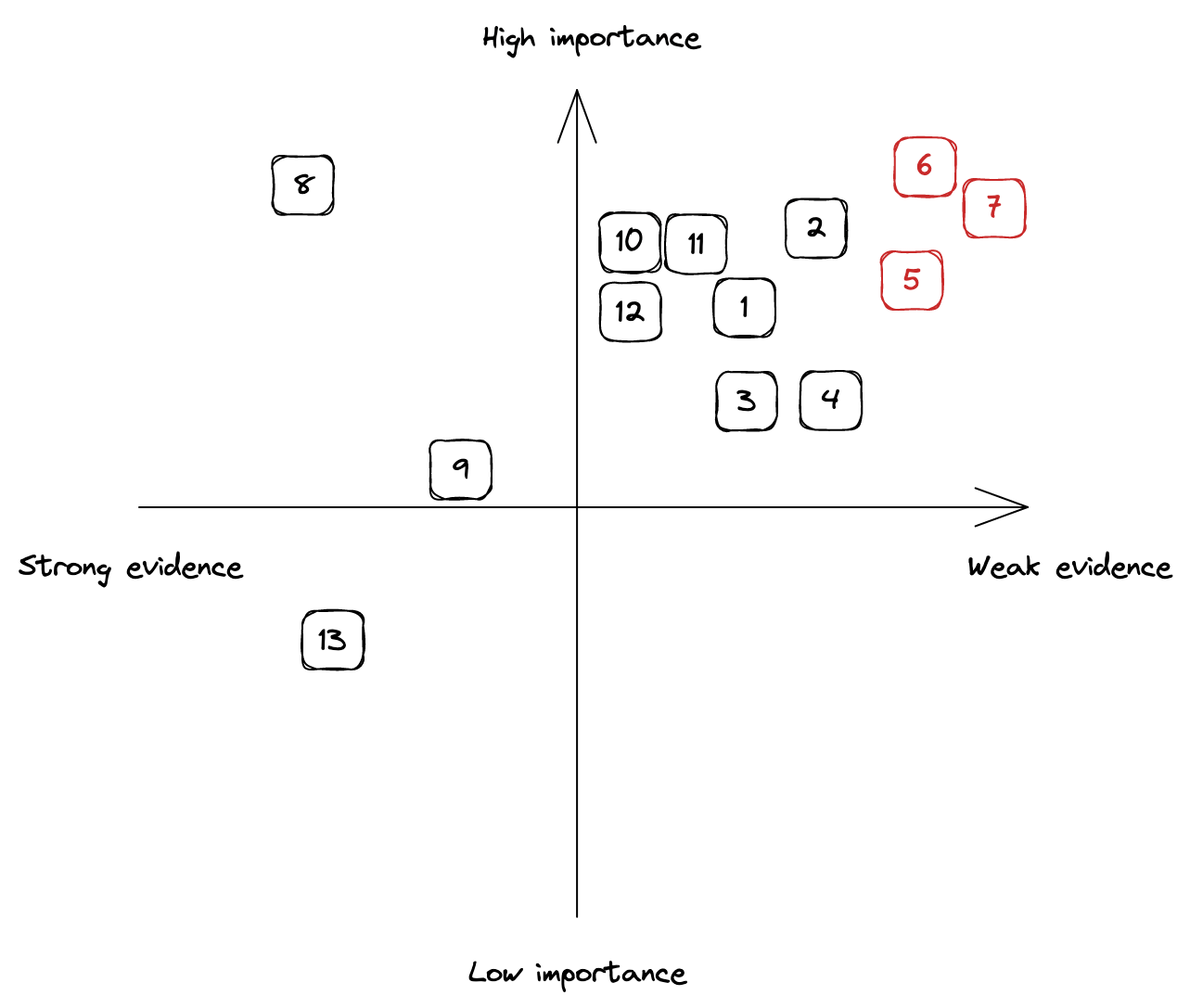

In the grand scheme of things, not all assumptions are equal; some can sink your idea whilst others are just details you should be aware of when fleshing out the business model/operations. An easy way to focus on the ones that matter is to map out these assumptions in a grid as below (importance versus evidence; evidence referring to how much evidence we currently have to prove/disprove the assumption) and select the top three that hold sway.

Assumption map (click to enlarge)

Assumption map (click to enlarge)

From this diagram, it appears as though assumptions #5, #6 and #7 are the ones that we should gather more evidence for.

Testing assumptions

The assumption → simulate → evaluate framework provides a roadmap for testing assumptions. Given that the goal is to reduce risk and not to prove an assumption as being true, the process is simple: pick one of your leap-of-faith assumptions, identify a moment you want to simulate, and evaluate the outcome against pre-determined criteria.

If, for example, I were to test assumptions #6 and #7 (‘There are enough schools that would pay for a digital solution’ and ‘We can easily reach and market to schools’), one way to accomplish that would be to create a fake brochure/website with a pricing plan, reach out to various school heads via different channels and assess what the response rate is (e.g., email sign-ups). If you have a pre-determined number of positive responses that would make the test pass (e.g., 5 out of 10 schools respond positively to our request), then that should provide a benchmark for you to know what success should look like. It will also give you an insight into the effectiveness of different sales/marketing channels and if you could scale via that channel.

How do you determine the correct response rate that should tip the balance? Unfortunately, the exact number is subjective and it’s best to arrive at one as a team. But it is important that you start small and then progress to large-scale tests. If you have an existing digital product and you want to assess the assumptions behind a particular feature, you could always run one-question surveys (e.g., ‘Do you want off-the-shelf assignments to pick from on our platform?’) or A/B tests as required.

If there’s one thing that you take away from this article, let it be this: don’t test whole ideas. When you are toying between a couple of ideas, identify the assumptions behind them and then devise tests to assess the risk of that assumption. That way, you can save some time, money and effort.